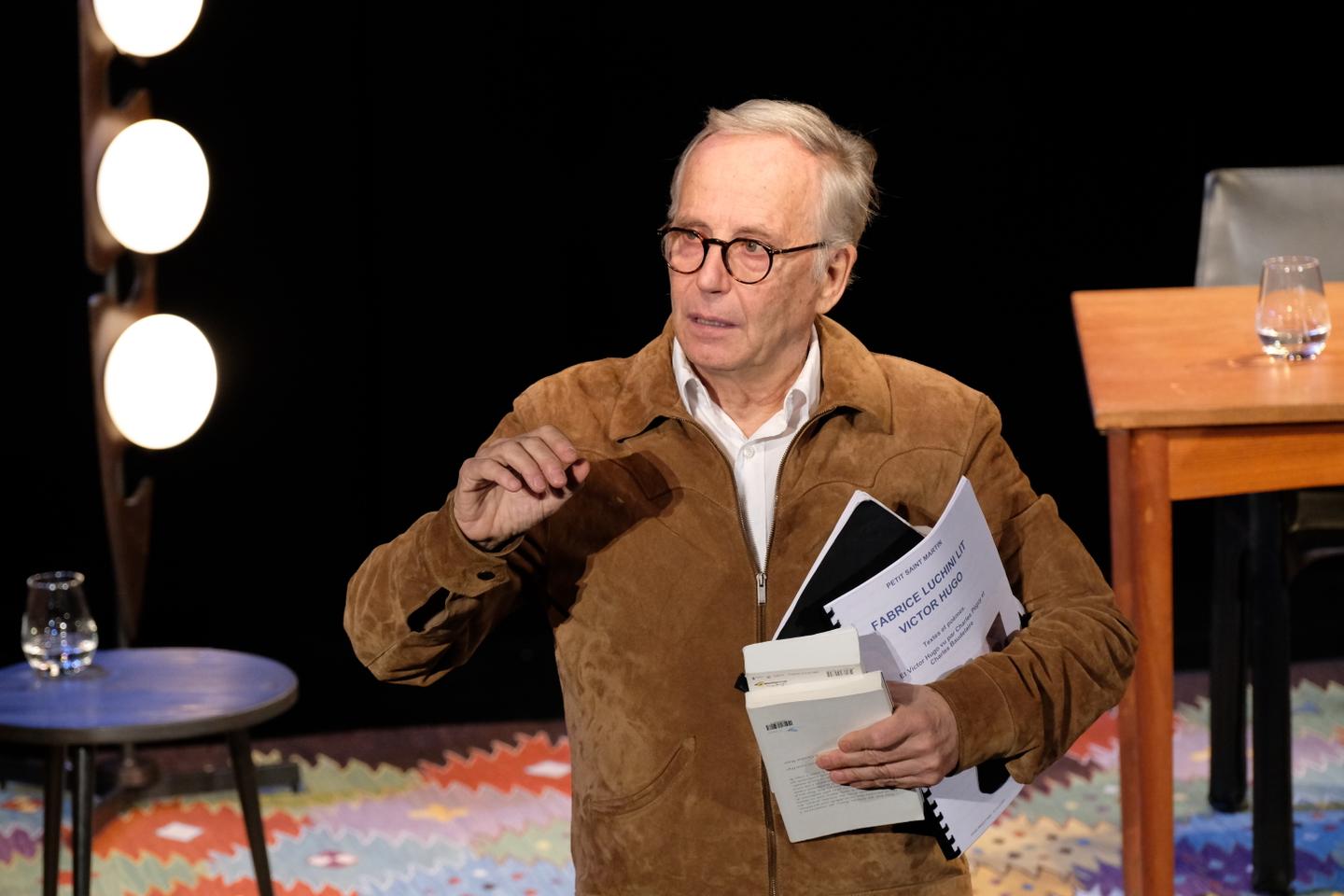

That Fabrice Luchini is a phenomenon is obvious. That he is above all an exceptional actor is the other certainty before which the audience bows at the Théâtre de l’Atelier, in Paris, where the last show of the artist is played (which he will perform again, from January 19, 2025, at the Théâtre de la Porte-Saint-Martin, in Paris).

Almost two hours of a wave of sensations, emotions and words where it is only about Victor Hugo. Hugo praised by Baudelaire and hailed by Péguy. Hugo, for whom the actor is careful not to build a mortuary marble statue (not his style), but which he makes stand, today, vibrant, sensual, human. More necessary to our lives than ever before. If we were to remember just one flash of this burning representation, it would be the imperative necessity of the wedding between poetry and humanity. A cliche? Yes, but who is undressed here: without poetry, humanity is poor in words, without humanity, poetry has nothing much to say.

How does the actor achieve this performance? In the first pages of Satin shoe (1929), an announcer appears to warn everyone: “Listen carefully, don’t cough and try to understand a little. What you don’t understand is the most beautiful, what is the longest is the most interesting, and what you don’t find funny is the funniest. » Paul Claudel is not called to the filming sets, but Fabrice Luchini could have mentioned him in the programmatic preamble. Not just because the audience stops coughing the moment he asks them to, in one of his unexpected addresses whose secrets he holds. But also because it creates an oceanic feeling in the room. He calls it brotherhood: “There are 600 of you in attendance every night, I’ve never experienced that”enthuses the actor.

An intangible communion

The truth is that around the literature led by Hugo to stratospheric heights an impalpable communion is formed and which the actor knows how to stage with a perfect art of suspense, anticipation and build-ups.

Less mutt than usual, sometimes even solemn and almost painful when Pastoral by Beethoven (“this deaf man who had a soul heard the infinite”), crumples and smoothes his manuscript, puts on his glasses, takes them off, rubs his left sleeve with his right hand, looks at the audience with the childish but sly eye of a patented seducer. His face is plastic. His voice wanders into confidences or invectives. He pretends to stutter, before saying the lines straight. He sits for a long time leaning on a wooden table, sits on a chair and then on an armchair. Three or four space trips, no more.

You still have 48.47% of this article to read. The rest is reserved for subscribers.