The title of an exhibition “Pop Forever” – “pop forever” – may seem excessive. Is this notion, pop, therefore timeless? Or, at the very least, should we ascribe to it a centuries-old longevity? Beyond display effect, without nuance, should it take its place among the categories in which the history and aesthetics of art have long delighted, such as classical or baroque? In order to be able to judge, we must start by defining this pop art, the principles, the goals, the means.

Which is not difficult, since several characteristics of various pop manifestations have appeared for a little over sixty years in many places. Therefore, we will call “pop art” all artistic representations of contemporary life as it has been revolutionized by countless scientific, technical and industrial advances, of which digital technology is only the most recent. Pop art is, in other words, the realism of the second half of the 20th century.e century and the beginning of the 21st centurye.

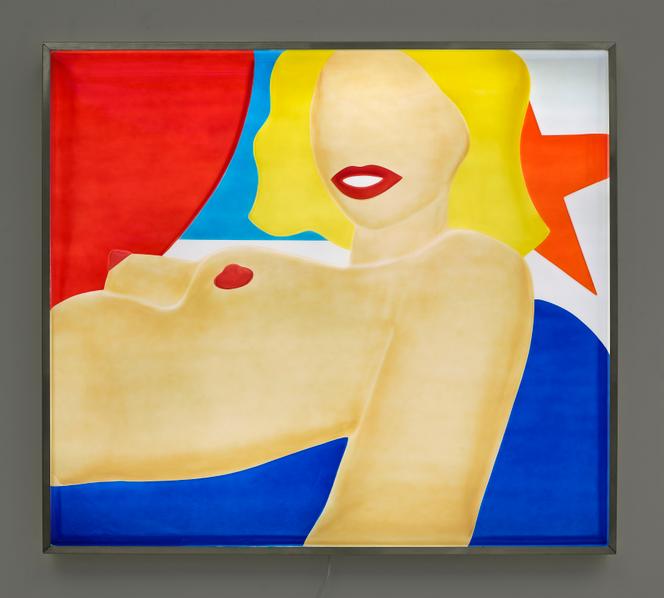

Since there was a pictorial realism of everyday life in Italy, Spain, the Netherlands, Flanders and France in the 17th centurye century (Caravaggio, Velazquez, Vermeer, the Le Nain brothers, etc.), and how there was a second one in the 19th centurye throughout Europe (Courbet, Manet, Menzel, etc.), a new realism emerged and spread after the Second World War, and that is what we have come to denote by this little three-letter word. It was first used in the field of visual creation before being taken over by the creative and music industry, with the risk of creating a lot of confusion. “Pop Forever” on display at the Vuitton Foundation is not about the Rolling Stones or David Bowie, but about Andy Warhol and his contemporaries, of whom Tom Wesselmann (1931-2004) is the central figure here.

Witness of societal change

Between the three manifestations of realism cited, there is an obvious difference. The first two are essentially pictorial, and the third is not uniform and, more often than not, proceeds differently, through collage, assembly, ready-made. It uses electricity and photo-based reproduction processes. Includes radio and TV screen sound.

Between a still life in oil on canvas or wood by the Dutchman Willem Kalf or Pieter Claesz, executed with mastery of light passing through glass or sliding on tile, and a still life by Wesselmann – who cultivated the genre a lot – the comparison can be surprising . It’s just that Kalf or Claesz bring together in their compositions objects, shells or fruits that, for their time, signified luxury, exoticism and the circulation of goods; and that Wesselmann brings together real or figurative objects such as bath towels, cans, and transistor radios that, in his day, signified comfort, consumption, and the flow of news and advertising. They therefore do the same work, which is to arrange on a flat surface or in bas-relief representative samples of the societies in which they live, whether in Paris and Amsterdam for Kalf, or in New York for Wesselmann three centuries later.

You still have 61.15% of this article to read. The rest is reserved for subscribers.